Full disclaimer: this article is not all encompassing. You could write a long book on foundation and endowment investment management. This is a collection of thoughts and opinions about what I think foundation and endowment boards should consider. If you’ve ever met me, you know I’m both opinionated and long-winded. So, if you serve on a board or work for a nonprofit foundation/endowment, don’t hesitate to send me an email and take me to task for why I’m wrong.

Board Composition

Nonprofit boards have a unique challenge often not faced by corporate boards. Members usually come from diverse areas of expertise, oftentimes without extensive investment expertise. If possible, I would strongly suggest boards do several key things:

- Form a dedicated investment committee and draft a charter. Boards should be especially mindful of:

- The overall size of the investment committee. Too large of a group will hamper coordination; too small of a group will not provide enough diversity of thought. A helpful rule of thumb may be five to nine members.

- Which positions are permanent and which rotate. Consider staggering member rotations and, ideally, using a minimum of five years of service. Gradual changes in membership balance both institutional memory and fresh perspectives.

- The expertise of those serving. Nonprofit boards should recruit someone with financial expertise beyond bookkeeping. In a best-case scenario, that’s a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA), but financial planners, trust officers, and accountants may have some investment knowledge.

Investment Policy

A strong investment policy should be an extension and reflection of the nonprofit’s mission. It should cover the following areas:

- Spending policy

- Investment purpose and strategy

- Portfolio construction

- Risk management

- Annual reviews

Spending Policy

I don’t like to pick favorites, but if I had to highlight the most critical area for nonprofits to focus on, it would be the spending policy. The best investment manager in the world will not save you from spending more than you earn. As such, your spending needs should dictate your investment strategy. Not the other way around. I would encourage boards and investment committees to ask themselves two important questions.

- How flexible can our organization be with spending?

- Have we stress tested our spending policy?

If your organization is fortunate enough to be flexible with spending, I usually see it in two forms:

- A simple percentage of portfolio value at the end of the prior calendar or fiscal year.

- A percentage of the average portfolio value over a specified term or a moving average (MVA). For example, each year’s spending may be equal to the average ending balance over the past three years.

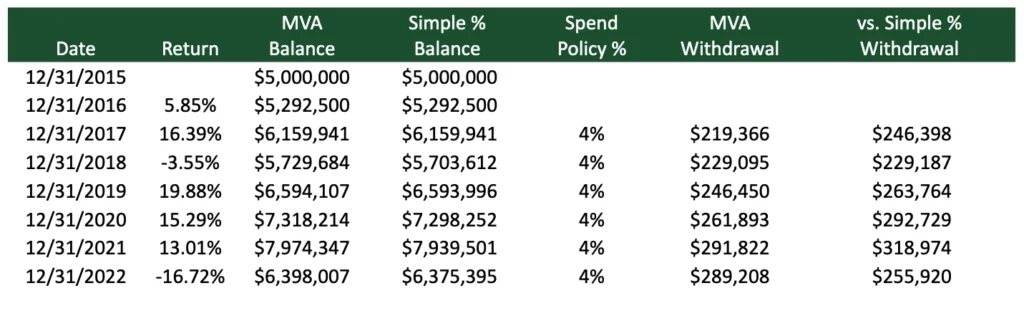

Unfortunately, neither of these approaches are conducive to consistent budgeting. Here’s a comparison of the two approaches below.

However, the MVA withdrawal moves much less from year to year. Following the simple percentage method, you can see a difference of roughly $63,000 from 2021 to 2022. That difference is only about $2,600 using the MVA method.

Many organizations don’t have the luxury of allowing their budget to vary so much from year to year though. Those organizations may opt to adopt a blended approach. For example, an organization could weight each method by 50% to provide a more predictable budget.

I mentioned stress testing your spending policy as well. What do I mean by that? Two important things:

- What do some of the worst-case scenarios look like for your organization? Is it a decline in contributions? A sudden unexpected expense? A decline in portfolio value?

- Quantify these worst-case scenarios with the help of your investment manager or a third-party consultant.

I would strongly recommend doing both of the above on an annual basis. Your investment manager can assist with forecasting these assumptions and how they affect your organization’s spending. Running these scenarios ensures both your investment committee and board are prepared for the worst.

Investment Strategy and Objectives

I’d argue most portfolios focus on one or a combination of three strategies:

- Capital preservation

- Real capital preservation

- Capital appreciation

In simpler terms: don’t lose money, don’t lose money after inflation, and grow the portfolio’s value. Most nonprofits we work with focus on numbers two and three. As I mentioned before, these strategies are dictated by your organization’s spending needs. Typical verbiage I would see in an investment policy might be:

“ABC Endowment is to be invested with the primary objective of real capital preservation with the secondary objective of capital appreciation while providing annual distributions as described in the ABC Endowment Spending Policy.”

Portfolio Construction and Risk Management

I am keenly aware I am at risk of getting far too technical in this section. Three rules of thumb to start us off:

- Most of your return is determined by your portfolio’s asset allocation. That is the ratio of stocks, bonds, and other investments in the account. That means picking the correct stocks or timing the market has very little effect in the long run.

- Use conservative return assumptions for your portfolio. It is very difficult, if not impossible, to accurately forecast returns. History is a helpful reference, but rarely indicates future returns.

- Risk and volatility matter. Many people seem comfortable with volatility until it actually happens. Your investment manager can provide you with portfolio stress tests. One 60% equity, 40% fixed income portfolio can have vastly different risk from another 60% equity, 40% fixed income portfolio.

Taking all the above into account, we believe the best approach to portfolio construction is intelligently allocating risk. That means determining portfolio percentages between three asset classes: equity (stocks), fixed income (bonds), and alternatives (more on this in a moment). Here is an example of a target allocation below:

| Asset Class | Subasset class | Target allocation | ||

| Equity | 60% | |||

| US | 45% | |||

| Non-US | 15% | |||

| Fixed Income | 40% | |||

| Investment grade | 32% | |||

| Below investment grade | 8% | |||

| Alternatives | See detail | |||

| Cash | 0% |

Since equities (stocks) tend to have higher returns than bonds, it is near impossible to maintain these target percentages without trading. A portfolio must be rebalanced. Rebalancing is the act of buying and selling assets to maintain the target allocation. It is one of the few free lunches available in investing. Ideally, it allows you to buy stocks when they’re cheap and sell them when they’re expensive. So, the obvious question, at what point do you rebalance? This is not a recommendation, but if I were on an investment committee with the allocation above, I would be comfortable with +/- 5 to 10%. In all honesty, if the investment manager(s) exceeded 5% under normal market conditions, I would be monitor them closely. The +/- 10% is for moments of extreme market turbulence.

Onto alternatives, the asset class I love to hate. I don’t even know if you can call it an asset class. To be clear, I don’t actually hate all alternative investments. The investment industry simply uses too general of a term covering too many different investments. Depending on who you ask, alternatives can span private equity, private credit, public/private real estate, public/private infrastructure, long/short equity, managed futures, market neutral, global macro, event driven, and more. Each of these are distinct asset classes with distinct characteristics. Some alternatives are extremely valuable, others can be a ploy to lock up your organization’s capital for high fees. Boards and/or investment committees should understand the role of their alternatives allocation before investing. If your investment manager plans on using alternatives, I would ask your investment manager the following:

- Will you describe the asset class?

- Has the behavior of this asset class been consistent across different economic regimes?

- Does the asset class increase or decrease risk?

- Does the asset class increase or decrease long term returns?

- Will this asset class affect portfolio liquidity?

- What are the average management fees for the asset class?

The list above is by no means comprehensive.

Measuring Performance and Benchmarking

Before we dive into technical jargon, the most important performance measurement is your portfolio’s ability to cover your organization’s spending needs. Investment management benchmarks are indexes that include multiple investments representing a portion of the market. The most well-known of these is likely the S&P 500 Index. So, when I review an organization’s investment policy, I like to see benchmarks divided into two categories: portfolio level and asset class level. Portfolio level benchmarks are for broad measurement and asset class level benchmarks are for specific measurement.

The portfolio level benchmarks I prefer are a static mix of indices tied to the target allocation. For example, 45% ‘US stock index,’ 15% ‘international stock index,’ and 40% ‘bond index.’ That means if your investment manager’s portfolio is 50% US stocks, 10% non-US stocks, and 40% bonds, the portfolio level benchmark will assist in measuring the performance and risk difference of the tilt toward US stocks

However, portfolio level benchmarks are not a great measuring stick for stock, bond, or fund selection. That’s where we would use an asset class level benchmark. Asset class level benchmarks are designed to illustrate skill (or lack thereof) at security (stock, bond, or fund) selection relative to a benchmark. For example, did the US stocks or mutual funds our investment manager selected outperform the S&P 500?

By using both portfolio and asset class level benchmarks, you can measure how proficient your investment manager is at both broad asset allocation and fund selection. As an aside, the former is much easier than the latter.

Annual Reviews

I’m a huge fan of lists, so we’re sticking to them. What should you review with your investment manager(s) every year?

- Investment and spending policies – modest changes over time may be needed.

- Asset allocation – ensure your investment manager’s asset allocation conforms with your investment policy.

- Investment manager performance – don’t put too much emphasis on a single year of

performance. I would encourage you to focus on three- and five-year figures. - Stress and scenario tests – as mentioned previously, do both at the spending and portfolio level.

- Investment manager costs – costs aren’t everything, but they are important. Check third party resources to ensure costs for your organization aren’t too high relative to peers.

Rules of Thumb

First, congratulations on slogging through my writing. You are among the coveted select few to make it this far. In fact, if you ever mention this to me, I will happily buy you a cup of coffee or a beer. I’ll leave you with three rules of thumb in closing:

- Focus on what you can control. You can’t control the economy or markets, and neither can your investment manager. Spend the bulk of your time creating a strong process that provides a sustainable financial future.

- Communicate. Send out agendas and presentations at least one week ahead of time. Be clear with your investment manager(s) on what you would like covered during their annual review.

- Do your homework and show up prepared. You or someone else on your team is responsible for someone else’s money. Listen, take notes, and ask questions.